for colored girls, a movin’ work

We had seen posters advertising the piece months before we headed to midtown; Shange’s face, as painted by Paul Davis, had been plastered around the city. We hadn’t seen a black girl’s body promoting anything literary since Kali published her book of poems, in 1970, at the enviable age of nine. You couldn’t have mistaken Shange, with her head scarf and multiple earrings, for a jive tastemaker; her style wasn’t very different from that of my four older sisters, who took African-dance classes and swore by “Back to Eden. — Hilton Als

I wonder if Ntozake Shange knew how prescient she was when, at the end of for colored girls have considered suicide when the rainbow was enuf, the cast intones, “this is for colored girls who have considered suicide/ but are movin to the ends of their own rainbows” (88). Since for colored girls . . . appeared on Broadway in September 1976, women have moved to “the ends of their own rainbows” by recreating the magic of fcg on college campuses and in theaters across the world.

Apart from naming and introducing to the world a new art form, one of the most fascinating things about the choreopoem is that is a “movin” work: it is composed of poetry written at different points of Shange’s life, it evolved as it moved from California to New York (and evolves today), and contains the seeds of the characters that appear in later works. “Beginnings, Middles and New Beginnings: A Mandala For Colored Girls,” Shange’s forward to the most recent edition, gives a beautiful account of the development of fcg and it’s relationship to the rest of her oeuvre. (I will upload the forward in Courseworks for those using the earlier edition.) You can also view a lively discussion about for colored girls (choreopoem and film) in a discussion between Ntozake Shange and Georgetown Professor Soyica Diggs (a former student of mine!) at the “Worlds of Shange” conference last year. She lets lose about the Tyler Perry film in the Q & A (at about 21). Let’s just be clear, if you have only seen the Tyler Perry film, you have not experienced for colored girls.

In the forward, Shange alludes to the “hateful response from African-American English speaking males” (10), which I remember viscerally as an ongoing attack on black feminist writers like Shange, Alice Walker and Michelle Wallace from the late 70s through the 80s (and residual today). We’ll talk about that when we discuss Wallace and the special issue of The Black Scholar devoted to Shange and Wallace.

Here are a few mixtapes. The first one I made myself of the music alluded to in “graduation nite.” There’s not a one-to-one correspondence because 8track didn’t have all of the pieces and sometimes there were modern remixes that I kind of liked. It won’t give up the embed code, but you can find it here.

SCALAR: Scalar is, in essence, a way to publish a richly visual “book” about a topic. Perhaps it is auspicious that we are starting Scalar training the same week that we read Shange’s most famous work. Although i’d be very disappointed if everything in our final site revolves around fcg, there is no denying that the choreopoem’s history offers enormous possibilities for visually compelling work. In a 2010 essay on for colored girls (quoted above), Hilton Als notes that for many people, the first impact of fcg was visual.

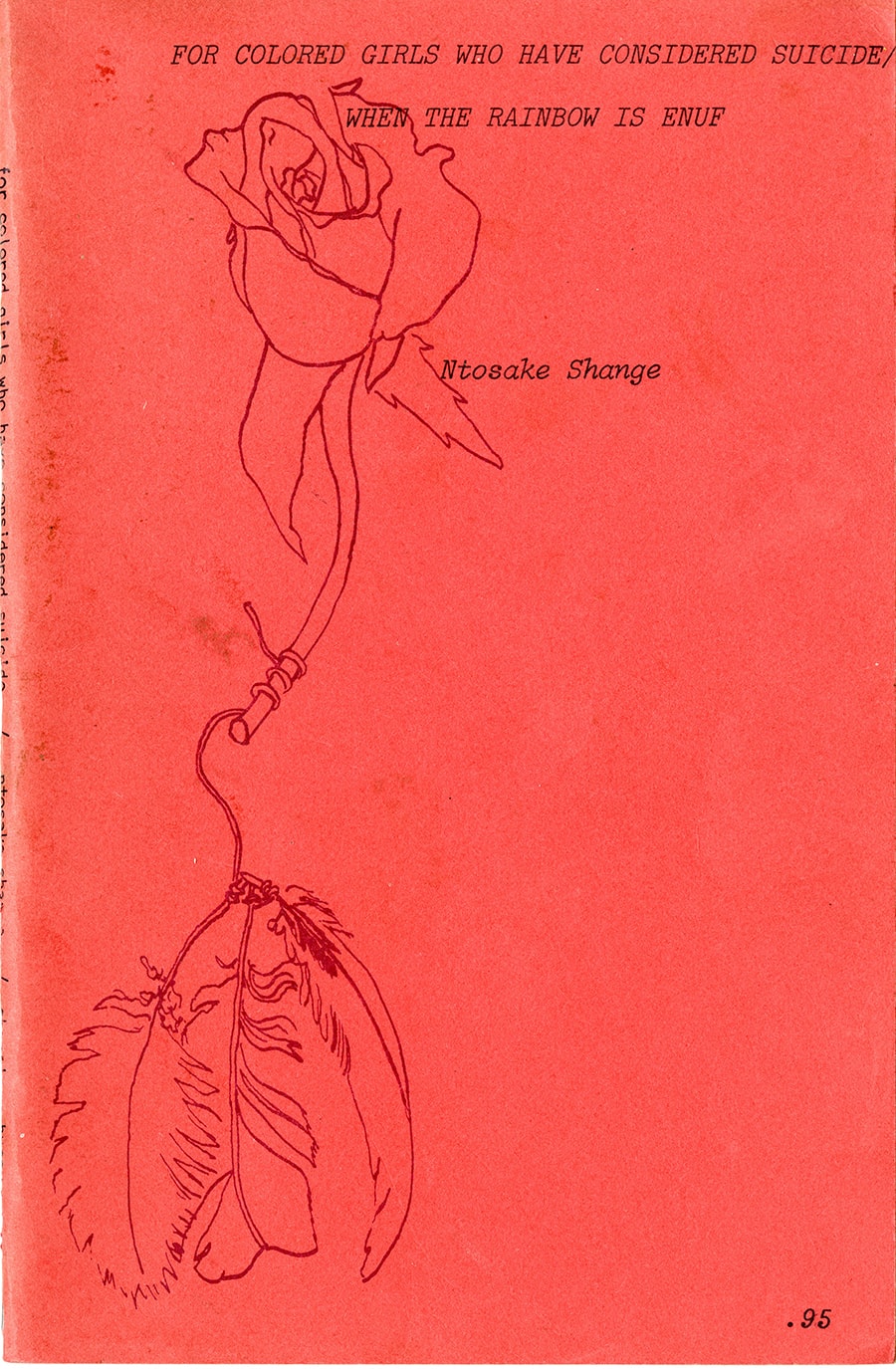

A couple of years ago, I google mapped the movement of for colored girls in NYC. What if someone created a map illustrated with archival materials? What could that teach us about the evolution of for colored girls in NYC from Afro-Latinx spaces to Broadway; from multicultural feminist spaces in Northern California to NYC? On the anniversary of for colored girls Hilton Als wrote an essay that focused quite a bit on the now-iconic for colored girls poster and how it resonated throughout the city. As you start going through the archive, think about what ways we can make your research visually compelling and communicative.

for colored girls performance venues, NYC, 1970s

Comments ( 9,432 )