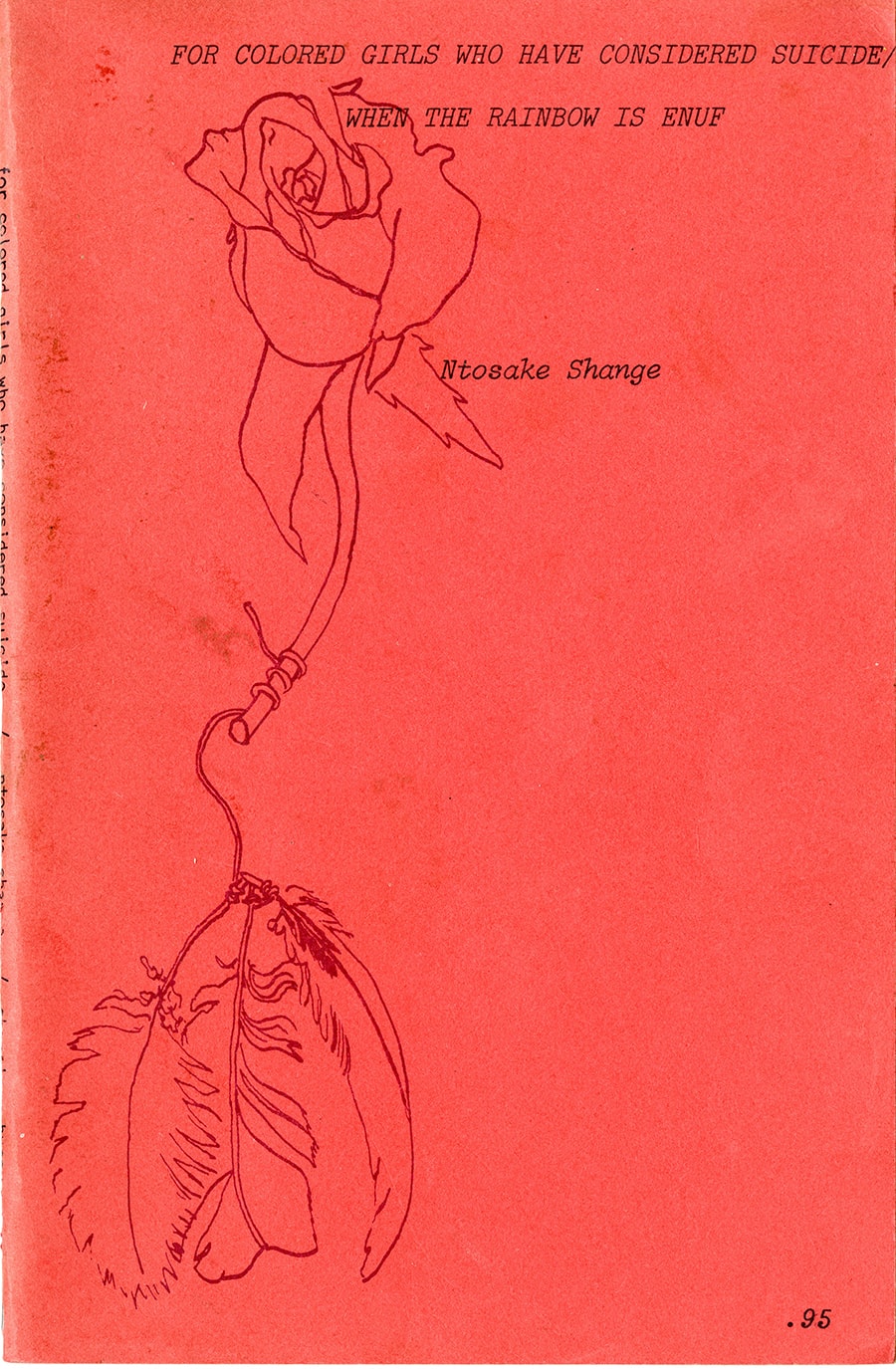

We have short-term and long-term planning to do at the beginning of class! We will be changing the syllabus to accommodate Shange’s visit on 10/22-10/23. Instead of going to the Schomburg, we’ll have our introduction to the Shange papers here at Barnard. (As I was reading the forward to for colored girls . . . and her description of “plundering notebooks” and calling friends in search of the “somebody anybody sing a black girl’s song” poem, it made me wonder in how many places Shange’s “archive” resides.)

Obviously, we’ve read quite a bit already, but I thought it might be nice to have a common reading we might discuss with her. A couple of (short) candidates:

1. From Okra to Greens: A Different Kinda Love Story, which A Daughter’s Geography says was originally performed by BOSS at Barnard College.

1. From Okra to Greens: A Different Kinda Love Story, which A Daughter’s Geography says was originally performed by BOSS at Barnard College.

2. boogie woogie landscapes, first presented as a one woman piece which scholar *Lester calls a “continuation of for colored girls”.

The longterm planning is more challenging. I have to schedule the Spring seminar. The ICP sessions are three hours. It’s possible (I think) to do it at our current time with an extra hour, but I’d like the brainstorm some possible times from between 8-5 since the Schomburg archives are only open during those times. Remember that we won’t be having regular classes towards the end of the semester.