CREATION IS

EVERYTHING YOU DO

MAKE SOMETHING

With this compelling order, I set out to create a zine.

During my reading of Sassafrass, Cypress and Indigo, I underwent a series of deeply personal transformations that I wanted to document. I became interested in creating a zine as an archival document. In it, I have included pieces of poetry and stories that I have written as well as pieces written by Shange herself. Creating a zine was a way that I could engage with the work in both tactile and spiritual ways and it illuminated some new aspects of what an archival process means. This archival process sometimes meant reading old love letters aloud. Or cutting out clippings from brochures I had been keeping as souvenirs from significant events.

My guidelines for creating a zine:

- Everything you do: to walk, and speak, and touch.

- Make something: rely upon the imagination, engage with memory, insert pieces of yourself into all that you do

The zine has come to life in its own way. It is an embodiment of places, things, memories. It is an ongoing project that I am using to explore different ways of creating literature, encapsulating memory, and fracturing the static notion of time. It has also pushed me to further interrogate the process of engaging with the personal as political and vice versa. How can my personal, intimate interactions with the world be mobilized as political tools?

This process of blending the personal and the political is a prominent aspect of Shange’s work. In this effort, Shange has often mobilized the feminine — imposing it upon the realms of art, politics, movement building and organizing. This isn’t merely a gratuitous mechanism aimed at making a “feminist” gesture, any feminist gesture, but a revelatory process. One that uncovers the deeply feminine impulses behind Black resistance, activism, and healing. These feminine impulses are situated in Black women’s knowledge and world-making practices. How we have learned to grow and survive relies upon the ways in which Black women have practiced knowledge and world-making through their crafting, cooking, singing, dancing, loving, birthing, mothering etc.

For me, a zine presents the possibility to build on the practice of creating and resisting via intimacy and the personal.

This podcast, by BCRW Research Assistant Michelle Chen, discusses the radical (anti white supremacist, anti classist, anti racist) feminist ideology from which zines have emerged.

“The Power of Craft”

The power of combining the mind and the body to create.

To do — to make do.

The power of the mind, the eye, the hand and the heart

To make the original connections.

TO create what is needed: a fire, a pot, a hoe, a knife,

A cup, shelter, cloth, tools.

To grasp

The significance of the power of craft

Is to be eager to create a whole life.

I found this in a Womanspirit publishing that was released during the Summer solstice 1982 while looking through the Barnard Center for Research on Women archives. The piece describes craft as a process that often melds the spirit and body to the object being created. The crafting process diverges from professionalized forms of creating art and is intuitively resistant to mass-production and manufacturing, making it inaccessible to commercialist impulses of capitalism. “The mind and the hand of the creator is part of the end product — “the spirit” of a work is apparent because of these unbroken connections.” (25).

Zines embody the spirit of craft in these feminine, anti-capitalist intuitions.

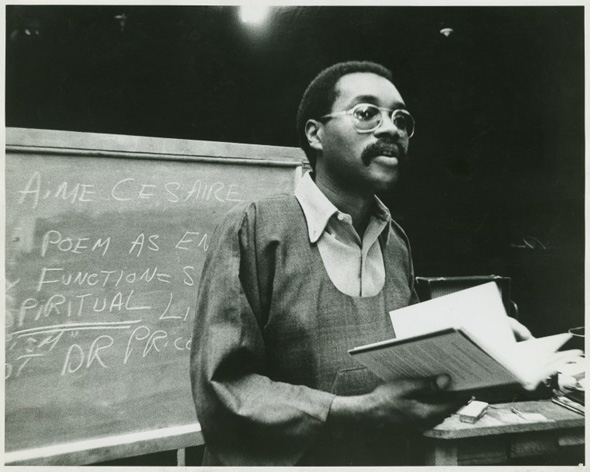

For the past few weeks, I have been thinking about the concept of being a daughter and how that is a motif in Shange’s work. My understanding of the saliency of (what I call) “daughtership” was further developed through my reading of Sassafrass, Cyprus and Indigo and during the Africana Department event “Who’s Going to Sing A Black Girl’s Song?” A Conversation on Black Girlhood with distinguished Africana alumnae Asali Solomon ‘95 and Alexis Pauline Gumbs ‘04.

For the past few weeks, I have been thinking about the concept of being a daughter and how that is a motif in Shange’s work. My understanding of the saliency of (what I call) “daughtership” was further developed through my reading of Sassafrass, Cyprus and Indigo and during the Africana Department event “Who’s Going to Sing A Black Girl’s Song?” A Conversation on Black Girlhood with distinguished Africana alumnae Asali Solomon ‘95 and Alexis Pauline Gumbs ‘04.